Let’s look at another state that offers some different features than Pennsylvania and Idaho did. Illinois is made up of regions that are run by universities and operate almost as mini-state programs in many ways.

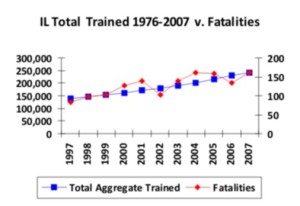

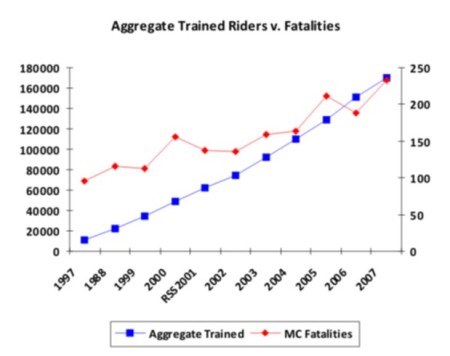

Training began in 1976 with 200 students and in 33 years, a total of 243,155 riders have taken basic training. In 1996, a total of 130,753 had already been trained. Iow, we know from Illinois what we didn’t know in Pennsylvania. However, I’ll figure it just as I did for PA—as if no one had been trained prior to 1997. And then, just because we can, we’ll figure the aggregate with the total numbers of basic trained students.

Illinois, too, switched over to the BRC but in 2002, but Illinois is also the only state that has field-tested TEAM Oregon’s curriculum for two years in two regions and an additional year in one of those two regions.

It’s a free state and only had a helmet law from 1967-1969 meaning there would be no sudden effect on fatalities as was possible in Pennsylvania.

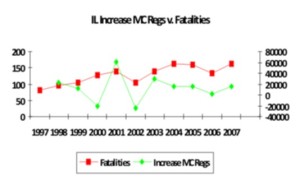

From 1997-2007, in Illinois:

MC Fatalities increased 96.34%

Training increased by 110.6%

Registration increased 81.7%

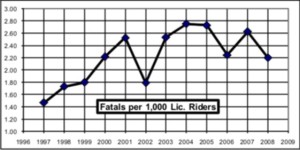

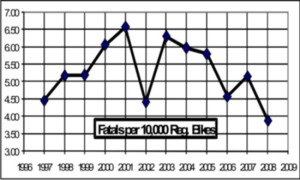

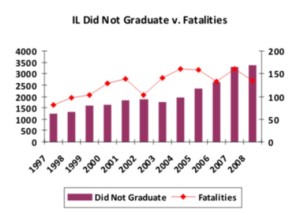

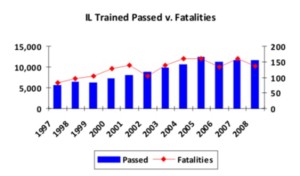

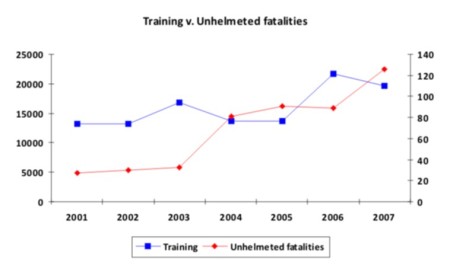

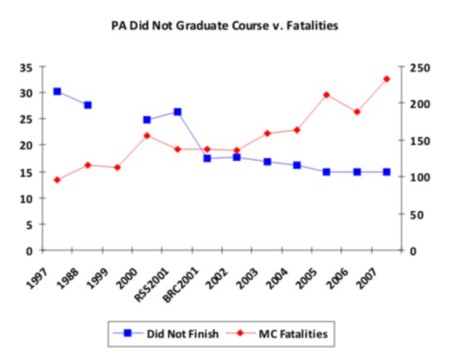

However, a former ILDOT administrator and current instructor in the UIUC region, Dave Taylor, prepared the following two graphs that were handed out at the spring Update:

John Sudlow, UIUC region project coordinator suggested that it appears that fatalities are no longer rising. While that would be good news, they are still considerably higher than they were back in 1997 per licensed rider—though not per 10,000 registered motorcycles. It should also be pointed out that it’s unknown whether Illinois includes off-road motorcycles in the total motorcycle registrations and what effect that would have on the registrations.

As illuminating as Mr. Taylor’s graphs are, we’ll go back to the apples to apples approach and look at Illinois as we did Idaho and Pennsylvania:

Training

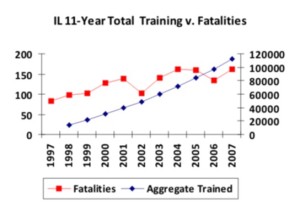

Training in Illinois as in the other two states showed a very strong upward trend over the 11 years.

Illinois was one of the first states to have an extensive motorcycle training program, developed two of the curriculums that MSF used as a basis for its curriculum and was one of the first states to sign a Rider Education Recognition Program contract with MSF. Illinois changed to the Basic RiderCourse in 2002.

- A total of 243,155 students have completed basic training from 1976-2007.

- Almost half of them (46%) were trained in that 11-year time span.

- 65% of those trained from 1997 were trained with curriculum based on student-centered, adult-learning principles.

Until recently, ILDOT counted students as “dropped” if they left the course before they completed 50% of the course. “Did not Graduate” however, has the net result which allows comparison between Idaho and Pennsylvania.

|

Year |

MC Fatalities |

Total Students |

Passed |

Failed |

Dropped |

Did not graduate |

|

1997 |

82 |

6,658 |

85.62% |

N/A |

N/A |

14.38% |

|

1998 |

97 |

7,311 |

80.30% |

12.40% |

4.50% |

16.90% |

|

1999 |

103 |

7,383 |

79.70% |

15.10% |

5.10% |

20.20% |

|

2000 |

128 |

8,458 |

81.40% |

14.20% |

4.40% |

18.60% |

|

2001 |

138 |

9,273 |

81.40% |

13.60% |

5.00% |

18.60% |

|

2002 |

103 |

10,052 |

82.60% |

12.20% |

5.20% |

17.40% |

|

2003 |

140 |

10,943 |

84.70% |

10.30% |

4.90% |

15.20% |

|

2004 |

161 |

11,828 |

84.80% |

10.50% |

5.00% |

15.50% |

|

2005 |

159 |

13,155 |

88.80% |

11.90% |

5.10% |

17.00% |

|

2006 |

133 |

13,007 |

80.90% |

13.80% |

5.30% |

19.10% |

|

2007 |

161 |

14,022 |

77.90% |

16.10% |

6.00% |

22.10% |

In the first years after the BRC began to be taught, the fail rate fell and the pass rate rose while the dropped rate stayed approximately the same. In this way, there’s a similar pattern in Illinois as we saw in Pennsylvania rather than what we saw in Idaho—but there’s not a huge difference in the percentages.

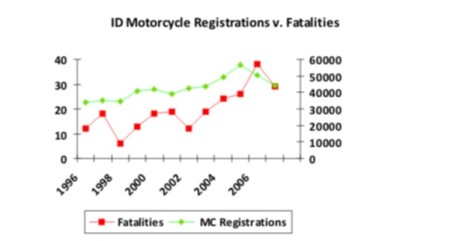

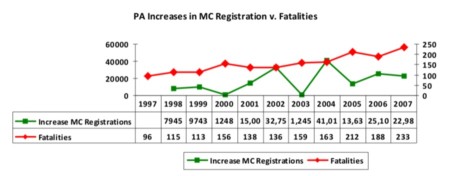

Does motorcycle registration explain the increase in fatalities?

Fatalities v. Motorcycle Registrations

Motorcycle registration alone did not explain the increase in fatalities in either Idaho nor Pennsylvania—but does it do so in Illinois?

Of note is the difference between the rate of fatalities by motorcycle registration and licensed rider and the raw number of fatalities v. the number of motorcycle registrations. It also appears Mr. Taylor used different figures than the ones available on the FHWA website. I am constrained to use FHWA stats to keep apples to apples with the other states we’re looking at, however the numbers are fairly close.

Looking at Illinois as we did Idaho and Pennsylvania, then, fatalities have leveled off, which isn’t as good of news but it’s better than if they were still rising.

However—as in the previous states—there doesn’t appear to be a strong correlation between increased fatalities and increased motorcycle registrations, which is what NHTSA has been saying for a number of years now though motorcyclists have continued to reject that notion.

Also of note is that, in all three states, motorcycle registration has gone up and down with greater or lesser swings while fatalities have also varied, the variations are far less pronounced.

Training and registrations

If we look at the increase in motorcycle registrations compared to the number of students who took basic training, in three of the four years, far more students took the course than additional motorcycles were registered and in an additional five years, there’s a significant overlap of students and registrations ranging from 59%-94%. Only in three of the 11 years were there a far greater increase in registrations than there were in students trained.

|

Year |

MC Reg Increase |

Total Students |

|

1997 |

10,708 |

6,658 |

|

1998 |

22,445 |

7,311 |

|

1999 |

12,424 |

7,383 |

|

2000 |

-21,122 |

8,458 |

|

2001 |

61,330 |

9,273 |

|

2002 |

-23,641 |

10,052 |

|

2003 |

28,856 |

10,943 |

|

2004 |

15,089 |

11,828 |

|

2005 |

14,971 |

13,155 |

|

2006 |

1,963 |

13,007 |

|

2007 |

14,960 |

14,022 |

As we know, some graduate training and do not ride, others fail and go on to get licensed anyhow or ride without licenses or are licensed without training and motorcyclists often own more than one bike. Even so, the aggregate number of students who have competed the course from 1976-2007 is 243,155 is just 30% less than the total motorcycle registrations in 2007.

This is the third state where we found what might be a correlation between training and motorcycle registrations.

If we apply MIC’s owner formula (1.5 motorcycles per owner) there’s more trained riders (243,155) at the end of this 11-year period than there were owners (231,533). This is the third state that we’ve seen trained students compared to owners or motorcycles are much closer than we’ve been led to believe they were. Common thinking—that most riders don’t take training—may not be true.

Once again, though, we have no idea how many fatalities have taken training in Illinois or somewhere else and we know there’s untrained riders on the road.

Still, as we’ll get to in a future entry—what it means that training numbers correspond more closely to the increase in motorcycle registration than fatalities do has critical implications.

Was one year a watershed?

2002 marks the halfway point between 1997 and 2007. It was also the year Illinois switched to the BRC:

In this subdivision of the relevant time:

- 65% of all the students trained in the relevant time period took training since then, and

- just under 50% of the increase in motorcycle registration occurred since 2002,

- But 75% of the fatalities occurred.

Which is not to say there are connections. But let’s look closer at training and fatalities:

Training and fatalities

Unlike Idaho, we don’t know how many trained students have died in motorcycle crashes.

However, unlike in Pennsylvania, we do know how many students have been cumulatively trained in Illinois. However to keep apples to apples, here’s the same comparison we did in other states—how many were training from 1997-2007:

However, because we do know exactly how many have been trained since the beginning of the program—as we did in Idaho—we’ll look at the aggregate trained v. fatalities:

Does this mean that training ultimately have no effect on fatalities—that Billheimer was right and absolutely all benefits from training is gone by the end of a year? Or does it just mean that training went up at about the same rate as fatalities but that’s just a coincidence? Or does it mean something else or nothing at all? I don’t know.

However, there is a difference when it comes to Did Not Graduate compared to fatalities and we don’t see the same pattern as in Pennsylvania:

If there is any relationship between fatalities and training—which is uncertain—it would seem to be much closer between those who passed the course and fatalities than those who did not:

This is not to say there are any relationships at all. It does suggest, once again, more study is called for.

For example, the percentages—overall—between the percentage of those who were passed or failed prior to the BRC and afterwards didn’t change all that much—however, just as in Pennsylvania, when Passed and Did Not Graduate are separated and compared to fatalities—there is a big difference and there’s a difference between the state that has a very low fail rate since 2002 and prides itself on telling its instructors not to be gatekeepers and encourage students to drop the course and the state that kept the same drop rate and ended up raising it’s fail rate towards the end and lowering its pass rate. Are these coincidences? I have no idea whether any of this means anything.

But there’s other interesting dimensions to Illinois’ fatality picture—more in the next entry.

Recent Comments